Answer the Question, Mr A. Rorschach

typed for your pleasure on 26 October 2009, at 6.11 pmSdtrk: ‘Tell her no’ by the Zombies

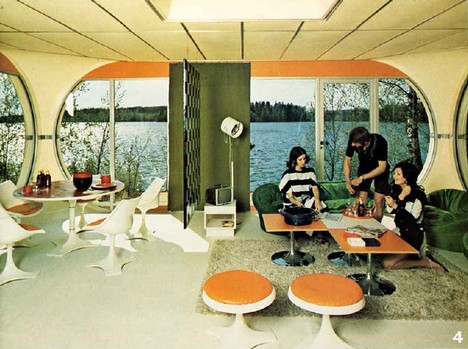

Don’t know what really put this into my head, but I thought of a really fab outfit to wear for any Hallowe’en parties I might attend. Wait, I don’t go to parties. Okay, perhaps for cosplaying. Wait, I don’t do that, either. Right; here’s an idea for a costume for use in a general Hallowe’en context. Stop interrupting.

All I’d need is

+ a white pair of dress shoes

+ a white pair of casual dress trousers

+ a white belt

+ a white shirt

+ white gloves

+ a white tie

+ a white single-breasted blazer

+ a white fedora

+ and a white facemask

and voila, I could go out as Steve Ditko’s Objectivist anti-hero, Mr. A!

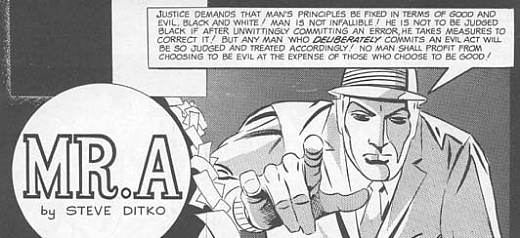

Yes, he talks like that all the time

Even though I’m not rabidly into comics, I love Mr. A, cos he’s such an extremely polarising character — you either love him or you hate him. Which is just how Mr. A himself would’ve liked it.

Back in 1966, comic book auteur and recluse Steve Ditko had left Marvel Comics, where he had brought the world Spider-Man and Doctor Strange, and was working for Charlton, a comic book publisher that has since vanished into history. One of the characters he originated during his tenure there was a gentleman called The Question, who was the alias of investigative journalist Vic Sage. When Vic went into vigilante crime-fightin’ mode, he would use a gas that would not only change the colour of his hair and clothes, but also adhere a rather creepy blank mask to his face.

The Question, crooning sweet nothings to his fans, as usual

Now, despite the blank face separating him from being a watered-down Batman, The Question was the first true comic book embodiment of Ditko’s Objectivist viewpoint. Ditko was an enormous fan of Ayn Rand, the Russian-born writer-slash-philosopher, who, in her own long-winded fashion, espoused the drive towards people being individuals that must shun not only the State, but any and all ideas of Collectivism. The original version of Vic Sage was a solitary crusader, often found righting wrongs in a corrupt society through a lot of punching.

In 1967, feeling that The Question wasn’t hewing close enough to the Randian ideal, Ditko wrote and illustrated a short story for a magazine called witzend, where he debuted Rex Graine, a newspaper reporter with the unforgettable alias of Mr. A. Whereas The Question might (note the word, ‘might’) let evildoers live when he caught them, Mr. A simply did not fuck around. He saw people in society as either being virtuous and harming no-one as they follow the path of Good, or immoral beings only intent on furthering their own corrupt goals; there was only black and white, with absolutely no shades of moralistic grey in between.

I’m just going to shamelessly rip a few paragraphs out of the Wikipedia entry on him, an act which would probably make me a criminal in the eyes of Mr. A:

Typical stories will have one character convince him or herself that doing just a few illegal acts to get ahead in life will not make him or her a bad person. This character’s crimes escalate when they must either take action to cover their previous misdeeds or are now too closely tied to more dangerous criminals to simply walk away. The stories invariably end with Mr. A confronting the criminals and telling them that they are all guilty, including the character who had wished to remain good. A staple for most stories involves this character trying to justify his or her immoral actions to both others and him or herself, blaming things such as environment and society rather than taking responsibility.

Almost every character speaks about the ideological reasoning behind their actions on every panel, thus showing that the adventure story is not meant to be just entertainment, but is to show an ideological dialogue and hopefully sway readers over to Objectivism.

Not all of Mr. A’s stories are crime adventures. Some are allegorical representations of the guilty trying to explain why they compromised their values. Mr. A, on a white platform, denounces their explanations. These stories typically end with the guilty falling into an abyss off of their black platform. This representation often occurs at the end of the adventure stories as well.

Critics have said that Mr. A is an unfeeling character who offers no remorse or mercy to criminals. In the stories themselves Mr. A says that he feels only for the innocent and victimized. His brand of justice might seem harsh to some, but on the other hand his punishments for criminals arguably fit the crimes they committed. People who commit “just one crime”, such as accepting dirty money are turned over to authorities to stand trial for what they have done. Mr. A refuses to overlook their transgressions, even if they profess they will be good from then on. Killers and would-be-killers generally find themselves in situations where they need Mr. A’s assistance to save them, but since they had no respect for innocent lives then he offers no aid for their guilty ones. It is only when an innocent life is directly threatened that Mr. A will kill, and when he does so it is without remorse.

In Ditko’s own way, a lot of the Mr. A stories remind me somewhat of Chick tracts, those kitschy Judaeo-christian fusions of morality and flat-out propaganda that you find in finer bus stations everywhere. You know — ‘you must do absolute good at all times, otherwise you’re going to Hell’. Mr. A’s just more immediate about it.

Incidentally, the character’s name stems from one of Aristotle’s statements, which is expanded upon by one of the characters in Rand’s ‘Atlas shrugged’: A is A. Meaning that a thing is a thing, and it can never be anything else. A doorknob will always be a doorknob; it will never be a sonic screwdriver, or a Bundt cake, or etc. Also, as the prototype for Mr. A was called The Question, Mr. A is the Answer, as in Q and A. Very clever, Steve Ditko.

Later in the Nineties, Ditko would be co-creator on his most important character to date, Squirrel Girl. But that’s a story for another time.

You’re at this point asking yourself, where does Rorschach fit into all of this? Simple! As I’d mentioned, Charlton Comics had dissolved around 1986; in 1983, DC Comics had bought the rights to a lot of the characters, one of them being The Question. Wild-eyed scary godlike genius writer Alan Moore was going to use some of those characters in a story he was developing at the time entitled Watchmen, but he ended up creating original characters based upon the Charlton heroes. Can you guess which one Rorschach was based off of? Go on, have a guess.

O Rorschach, you so crazy

So yeah! You have to love Mr. A and his overbearing monomania. Incidentally, as Mr. A’s appearances are desperately out of print, ‘Dial B for Blog’ wrote a fantastic three-part article on him, which features excerpts from his first appearance. Utterly compelling.

Now as obscurely fantastic as dressing up as Mr. A would be, to make the whole effect really come together, I’d have to recite a lot of boilerplate Randian-type talk for whenever I spoke in character, which could either be hilarious or ugly.

HOST: Hey there… ah, Good Humor Man? Have you tried the punch? It’s my special recipe!

‘MR. A’: Sorry, I’m not drinking.

HOST: Oh come on, loosen up a little! It’s ju *gets decked*

‘MR. A’: NO MAN HAS THE RIGHT TO DICTATE TO OTHERS HOW TO LIVE OR WHAT TO CHOOSE! IT’S EITHER ONE SIDE OR THE OTHER! IF YOU SUPPORT EVIL THEN etc etc

Which leads me to ask which would be scarier / more effective: dressing as and being in character as Mr. A, or dressing as and being in character as Rorschach?

Technorati tags: Steve Ditko, Objectivism, Mr. A, Marvel Comics, Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, Charlton Comics, The Question, Ayn Rand, Jack T. Chick, Atlas Shrugged, Aristotle, Rorschach, DC Comics, Alan Moore, Watchmen, Squirrel Girl

Random similar posts, for more timewasting:

To keep him fresh, duh on July 19th, 2004

Doing their part to Advertise and Confuse on October 30th, 2004